Mrs. Frank (Apolline) Blair

Mrs. Frank P. (Apolline) Blair

Founder of St. Louis Children’s Hospital

Birth: Sep. 14, 1828, USA

Death: Sep. 5, 1908, USA

Family links:

Spouse:

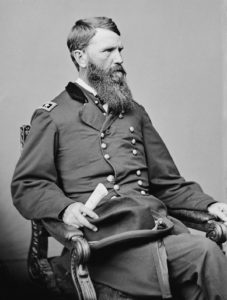

Francis Preston Blair (1821 – 1875)

Children:

Andrew Alexander Blair (1848 – 1932)*

Christine Biddle Blair Graham (1852 – 1915)*

James Lawrence Blair (1854 – 1904)*

Francis Preston Blair (1856 – 1914)*

Cary Montgomery Blair (1867 – 1944)*

Eveline M Blair (1870 – 1876)*

William Alexander Blair (1873 – 1898)*

The 1875 Compton and Dry map resident lists include very few women. Usually, only widows of great men are listed at the specified addresses. This is the case of Apolline Blair. Her husband, Major General Francis P. Blair, died in July of 1875. Often, the widows listed lived remarkably productive lives of their own. This is the case for Apolline Blair.

Wife of Major General Francis P. Blair, Jr, Apolline Alexander Blair, widow of Civil War general and later Senator Francis P. Blair, Jr., was the organizer and first president of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Board of Managers. In the winter of 1878, Blair gathered a group of 20 prominent women to discuss the plight of poor, sick children. Having lost two children to infectious illness, Blair was especially aware of the need for hospital care for children. Though there were established hospitals to care for the poor, children were excluded because the hospitals lacked the staff and facilities to care for them. Blair proposed to her friends that they begin a fund drive to establish a children’s hospital to provide medical and nursing care for needy children. They organized themselves into a Board of Managers and raised $4,500 to purchase a building at 2834 Franklin Avenue. The certificate of incorporation that was filed on May 6, 1879 named only women: Apolline Blair, Mary W. McKittrick, Caroline B. Treat, Margaret H. DeWolf, Rebecca Webb, Cherrell W. Parker, Virginia E. Stevenson, and M. Louise Norris. The hospital opened on October 29, 1879. Blair led the Board of Managers until 1883. She continued to serve on the Board, often as an officer, until her death in 1908 at the age of 80.

General Francis Preston Blair

History of St. Louis Children’s Hospital

In 1878, a group of 10 women gathered for an afternoon tea. This meeting was much more than a social occasion, however. It would prove vital to the creation of a St. Louis landmark – St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

As they sat in a parlor of a house at 2737 Chestnut St., they listened to the hostess, Mrs. Apolline A. Blair. She was the widow of former Army General and U.S. Senator Francis P. Blair Jr.

Mrs. Blair presented an exciting new idea – a plan for St. Louis to have a hospital where children could receive the special care they needed and deserved. Like many women of her time, she had lost one of her own eight children, a 6-year-old daughter, to illness.

Early Advocates for Children’s Health

Also in attendance were four of the area’s leading homeopathic physicians. Homeopathic medicine was a controversial form of treatment using tiny doses of natural drugs designed to stimulate the immune system by producing symptoms like those of the disease itself.

The homeopaths had often seen the suffering of children who were victims of injury or disease, compounded by poverty, malnutrition and neglect. It was time, they said, to establish the first hospital in the city specially geared for children. To bolster this effort, the physicians would volunteer their help. But they needed additional financial help.

The women in attendance were enthused, and during the months that followed they worked hard seeking donations for the new hospital. Eventually they raised $4,500 – enough for the first hospital building.

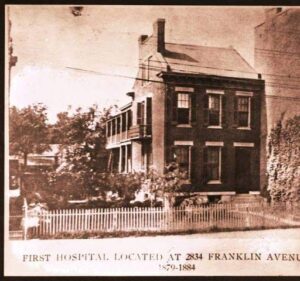

First Children’s Hospital in 1879

Bricks, Walls, Medicine… On October 29, 1879, the dream became reality. A 15-bed hospital, with a qualified matron in charge, opened at 2834 Franklin Ave. in St. Louis. Its first two patients were a crippled boy and a blind girl.

The name of the new facility: St. Louis Children’s Hospital – an all-embracing and non-committal name for the new venture.

An excerpt from the hospital’s first by-laws stated the new institution’s role quite simply: “The object of the Board of Managers of St. Louis Children’s Hospital shall be to maintain an institution; non-sectarian in its management and its benefactions; for the treatment of children from birth to 14 years.

Growing, Moving, Expanding

The original Board of Managers consisted entirely of women. This reflected a popular belief at the time that women were particularly suited to any endeavor affecting children – be it personal or institutional. Women who were not themselves professionally trained in medicine nevertheless played an important role in the organization of St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

Growth came quickly for the institution. By 1884 it had outgrown its first quarters, and its benefactors were raising money for a new 60-bed hospital at Jefferson and Adams in downtown St. Louis. A few years later they raised enough money for a three-story addition.

In 1894, an afternoon kindergarten was established for the convalescent children there. Training for nurses in the diseases of infants and children began in 1907 at the hospital.

Children arriving at Children’s Hospital

The first steps for the hospital’s next move were taken in 1912 when a lot at 500 South Kingshighway Boulevard was purchased for $26,122. Three years later, a new facility opened at that location, now affiliated with Washington University.

The Kingshighway site was expanded in 1922 and again in 1952, bringing the total number of patient beds to 165. Later, a 10-story structure, Spoehrer Children’s Tower, added 70,000 square feet of space to the complex and eventually brought the number of hospital beds up to 182.

The baby boom eventually required a move to a completely new building in 1984. Located a half-block north of the old hospital (since demolished), the new facility offered more than twice as much space and 235 beds.

Pioneering Pediatric Care in the Region and Beyond Progress at the hospital is not measured in just bricks and mortar. St. Louis Children’s Hospital, in conjunction with its academic and physician partner, Washington University School of Medicine, achieved many clinical milestones as well:

-

From 1915 through the 1920s, Dr. Vilray Blair, known as the father of plastic surgery in America, perfected several important methods for correction of cleft palate and cleft lip.

-

At about the same time, Dr. W. McKim Marriott, the hospital’s Pediatrician-in-Chief from 1917-1936, revolutionized the artificial feeding of infants, developing a formula using evaporated milk, corn syrup and lactic acid supplemented with vitamins and iron.

-

In 1922, for the first time anywhere, insulin was used to successfully treat an infant with diabetes. In 1927, Dr. James Barrett Brown performed the first homograft on a child resulting in the development of modern care for burns for children.

-

In 1929, Dr. Alexis F. Hartmann developed the first practical treatment, Lactate Ringers Solution, for infants suffering from severe diarrhea and dehydration. Dr. Hartmann served as the hospital’s Pediatrician-in-Chief from 1936-1964.

St. Louis Children’s Hospital pioneered developments in many other health areas, including diagnosis of congenital heart diseases. After the acquisition of a heart-lung machine in 1958, the hospital became one of the most active institutions in the country in the field of pediatric open-heart surgery. David Goldring, MD, who formed the hospital’s cardiology division in 1950 and remained its director until 1985, was a pioneer in pediatric open heart surgery. In another “first,” doctors oversaw the first complete exchange of blood in a tiny infant weighing less than 3 pounds.

The first pediatric dialysis unit in the Midwest was set up at SLCH in 1974. Another innovation during the 1970s was the establishment of the Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Deformities Institute, the only one of its kind in the Midwest at the time. This unit works with many other areas of the hospital to reconstruct head and facial deformities in children.

Clinical milestones continued in the 1980s. For example, Dr. Thomas Spray, a cardiothoracic surgeon, performed his first successful Norwood procedure, an advanced surgical technique used to correct the fatal congenital heart defect known as hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Doctors at St. Louis Children’s Hospital also performed the region’s first cochlear implant, surgically implanting a device the helps children who are deaf to speak and comprehend language.

Today’s St. Louis Children’s Hospital

Today’s St. Louis Children’s Hospital

The 1990s saw an expansion of the hospital’s organ transplantation program. SLCH established the first free-standing pediatric lung transplant program in the United States. Today, St. Louis Children’s Hospital is home to the world’s most active pediatric lung transplant program. The hospital is one of the nation’s leaders in total pediatric organ transplants, offering kidney, liver, heart and bone marrow transplant programs as well.

Such outstanding treatment and care has led to more patients being seen from all 50 states and nearly 50 countries around the world. Through the years, national publications such as Child magazine and U.S. News & World Report consistently list St. Louis Children’s Hospital among the very best children’s hospitals. Hospital programs receiving national recognition include newborn intensive care, cerebral palsy, burn care, asthma care and transplantation.

Today, national and international centers of excellence include the world’s largest pediatric lung transplant program, the largest team of pediatric epilepsy specialists, the most comprehensive cerebral palsy center in the country, and the world’s largest selective dorsal rhizotomy surgical program for children with cerebral palsy.

St. Louis Children’s Hospital remains fiercely committed to Appoline Blair’s vision of helping poor, vulnerable children in the community. (from the history of St. Louis Children’s Hospital – stlouischildrens.org