Creating an Impossible Map

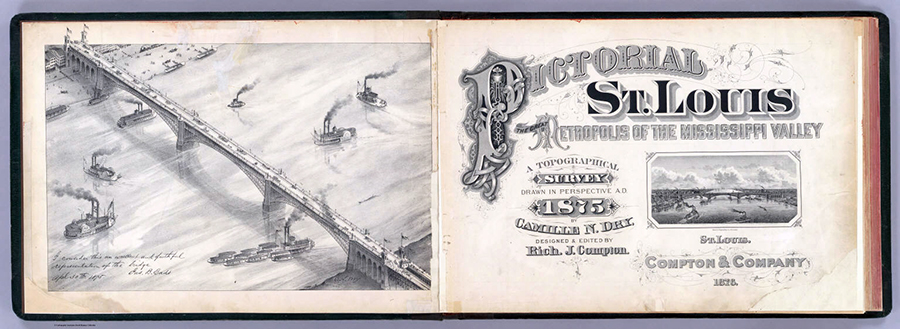

This Lucas and Garrison project was inspired by the St. Louis topography maps drawn by Camille N. Dry and designed and edited by Richard J. Compton in 1875. The map-making project was monumental in its detail and accuracy. As the scope of the work is examined today you would have to say the feat was impossible, except that the maps exist. The compilation and presentation of the map’s 110 sections or plates begins with a preface written by the creators when the maps were published in 1875. Their words appear here:

The preliminary drawings for this work were made early in the spring of 1874. After a careful consideration of the subject, it was determined to locate the point of view so that the city would be seen from the southeast, believing that to be the most advantageous in all respects. Accordingly, the point of site was established on the Illinois side of the river, looking to the northwest, and at sufficient altitude to overlook the roofs of ordinary houses into the streets. A careful perspective, which required a surface of three hundred square feet, was then erected from a correct survey of the city, extending northward from Arsenal Island to the Water Works, a distance of about ten miles, on the river front; and from the Insane Asylum on the southwest to the Cemeteries on the northwest. Every foot of the vast territory within these limits has been carefully examined and topographically drawn in perspective, by Mr. C. N. Dry and his assistants, and the faithfulness and accuracy with which this work has been done an examination of the pages will attest. Absolute truth and accuracy in the representation of the territory has been the standard and in no cases have additions or alterations been made unless the same were actually in course of construction. In a few cases, important public and private edifices that are not yet finished are shown completed, and as they will appear when done. All the buildings within the limits of the survey in July, 1875, are shown; and a very large number of those executed or commenced since that date have been also introduced, the pages having been constantly corrected up to the last possible moment before publication.

In dividing the work into pages, it will be seen that in, cases where a building is but partially drawn on one page, it is given complete on the adjoining page. In view of the magnitude of the work, the originality of the idea, and the difficulties encountered in carrying it out, it is hoped that if any mistakes or errors have crept into the plates or pages, they will be looked upon with a lenient eye by an indulgent public.

St. Louis, December 20, 1875.

As observers of the maps these 140 years after they were published, we certainly can be lenient. Actually, we can be in awe. The sophistication, detail and artistry of this endeavor is legendary.

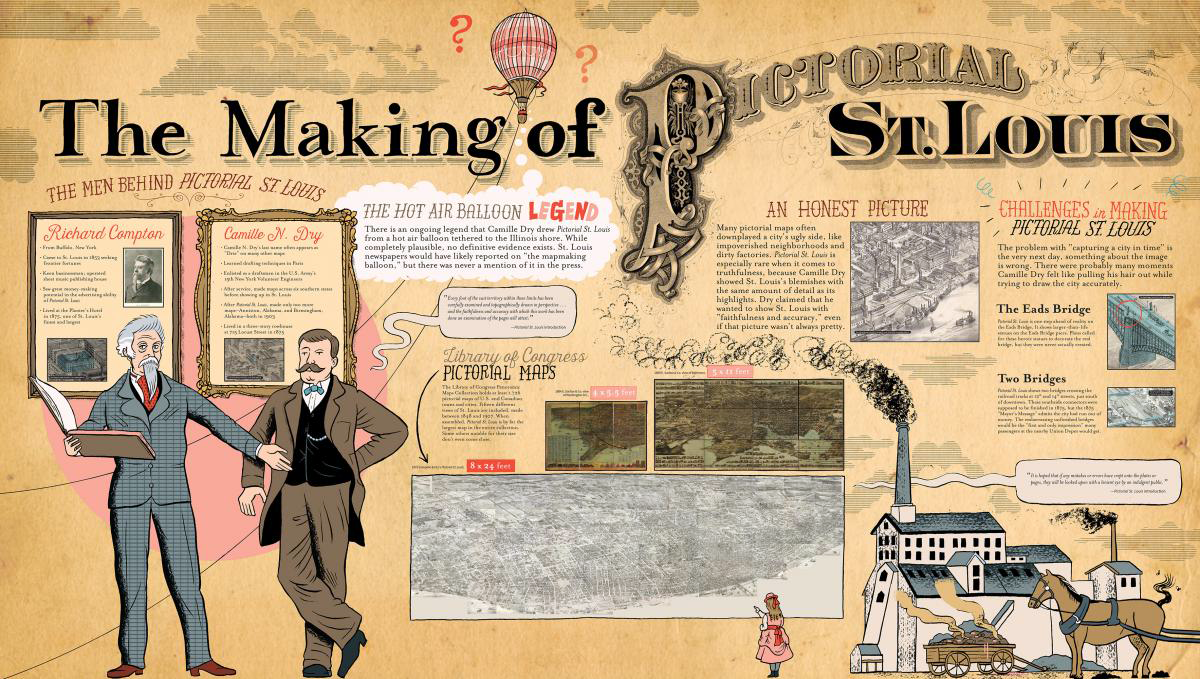

The Making of “Pictorial St. Louis” was a featured exhibit at the Missouri History Museum in 2015.

Who Was Camille Dry?

Camille Noel Dry was born on Christmas Day 1842, in Vielverge, Cote D’or, France. He received a diploma from the Conservatorie National des Arts and Metiers in Paris in August 1858, presumably for some sort of mechanical drafting. He came to the United States in August 1864, during the height of the Civil War, and enlisted in the U.S. Army Company F, 15th New York Volunteer Engineers. He served with the company as a draftsman until May 1865, when the war ended. His name disappeared for a while, and then reappeared in July 1870 when he married Ms. Carrie Block in Louisiana. With his new bride and a young son, Dry spent the next three years bouncing across six southern states making panoramic town maps.

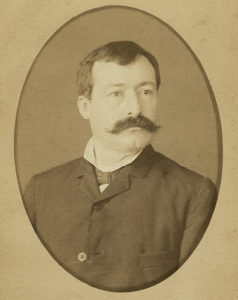

Dry’s earliest maps show an artist still developing skills, working through a shaky understanding of perspective and aesthetic. His maps of Columbus, Mississippi (1871); Columbia, South Carolina (1872); and Raleigh, North Carolina (1872), show great technical ability, but they look flat and stiff compared to the active landscape of Pictorial St. Louis. He would hone his skills as he worked his way across the South in late 1872, drawing Charleston, South Carolina, and Macon and Augusta, Georgia. His single work of 1873 was a ship-filled view of Norfolk, Virginia, and soon after he headed to St. Louis for the biggest project of his career.Camille Dry in his later years

In the early spring of 1874, Dry arrived in St. Louis to begin preliminary sketches for Pictorial St. Louis. Dry was a remarkably fast worker—between 1871 and 1872, he made panoramic maps of eight cities in five different states—but the enormous scale of Pictorial St. Louis was unlike anything he, or anyone else, had ever attempted. It is nearly certain that Camille Dry did not produce Pictorial St. Louis alone, but had a team of artists working simultaneously. Just how many is not known, nor is it known how they were organized. The team of artists went to incredible lengths to depict the landscape accurately, and it is noted in the book’s introductory pages: “Absolute truth and accuracy in the representation of the Territory has been the standard.”

The final product, Pictorial St. Louis: The Great Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley, A Topographical Survey Drawn in Perspective A.D. 1875, sold for $25 (about $530 today). Many copies were sold through advance subscriptions and newspaper advertisements, but the map’s enormous price tag ultimately made it a financial wash. Dry seems to have suffered a severe case of cartographer’s burnout. After Pictorial St. Louis, he made only two more panoramic maps—views of Anniston and Birmingham, Alabama —nearly three decades later in 1904.

(History Happens Here – Missouri History Museum Blog 5/26/15)

Let’s Consider the Realities of the Project.

Think about your neighborhood, or more specifically, the square block on which you live. How many houses or buildings are there on that block? Does each one have distinctive features in architecture, dimensions, landscaping and relationship to adjoining properties? Now imagine creating a pen and ink sketch of the block using nothing but, remarkably, pen and ink. The more detail the better, and almost good enough in representation is not good enough. The drawing needs to be an exact representation. And, by the way, we need the drawings to be done from a bird’s eye view with accurate perspective. How long would it take you to accomplish that task? I’m exhausted just thinking about it.

Now let’s consider the Dry and Compton 1875 map. Each map contains on average between 35 and 40 square blocks such as the one block we just contemplated. The detail on each building, the streets, parks, pedestrians and vehicles is extraordinary. Each building is an accurate work of art. The completed rendering of each area represented on the map was reduced to a single page format of 18.76 by 12.46 inches yet all of the detail is unbelievably resolute in its publication. Only a magnifying glass proves out the detail. Now take that one map and multiply it 110 ten times in order to encompass the total of the city of St. Louis in 1875 – every street and every building. It’s impossible.

How Did He Do It?

This was the early 1870s. Photography was very rudimentary by our sophisticated smart phone standards – large heavy box cameras needing the support of substantial tripods and long exposure times. Because of the remarkably accurate perspective captured in the photos used as the framework for the final drawings, it is thought that the pictures were taken in a hot air balloon suspended South East of the city, across the river over Illinois.Capturing as much data as he needed for the actual drawing would seem to take an impossible amount of time. And imagine trying to correctly expose photographs in an unbalanced and moving balloon.

Even when that was accomplished, it would seem that every building would have to be examined separately in order to capture the detail presented on the maps. The drawings have been compared to early photographs of individual buildings and the number and placement of windows, doors and decorative architecture is absolutely correct.

Even when that was accomplished, it would seem that every building would have to be examined separately in order to capture the detail presented on the maps. The drawings have been compared to early photographs of individual buildings and the number and placement of windows, doors and decorative architecture is absolutely correct.

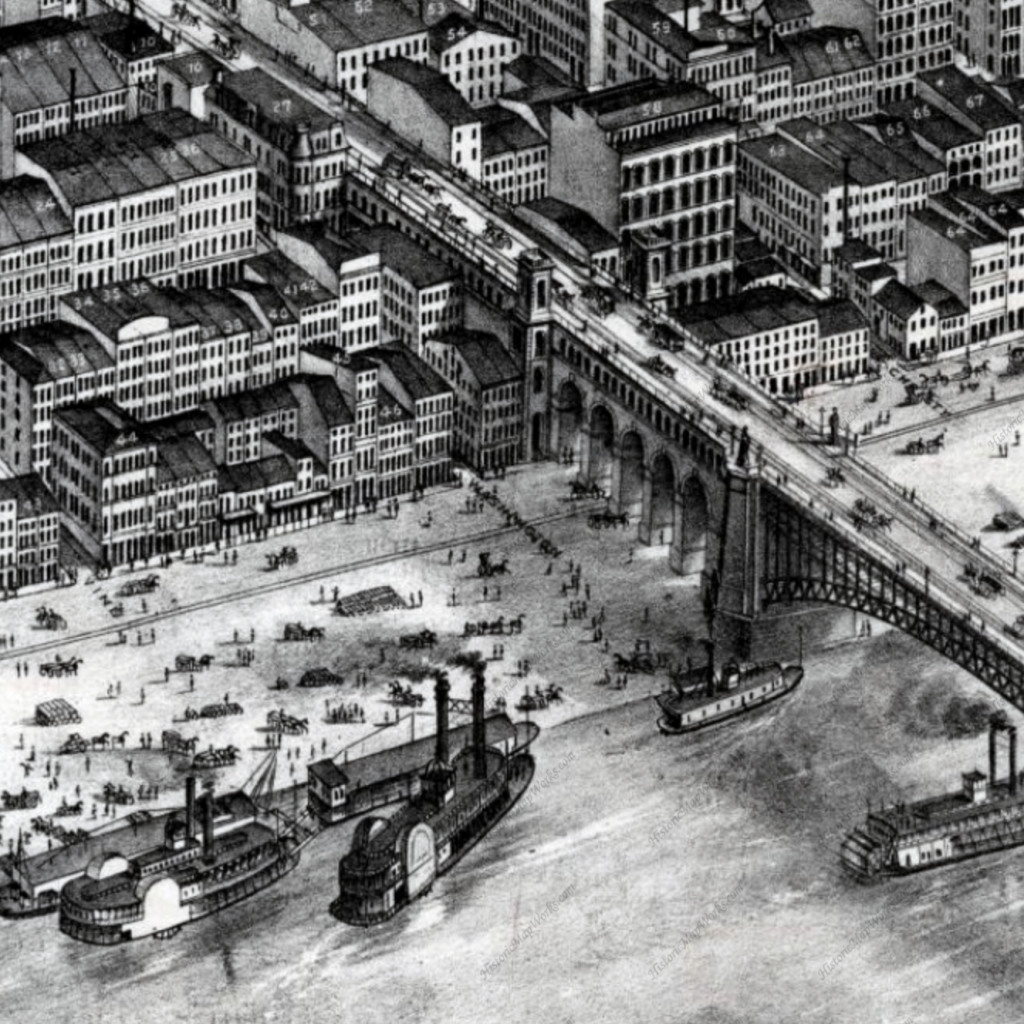

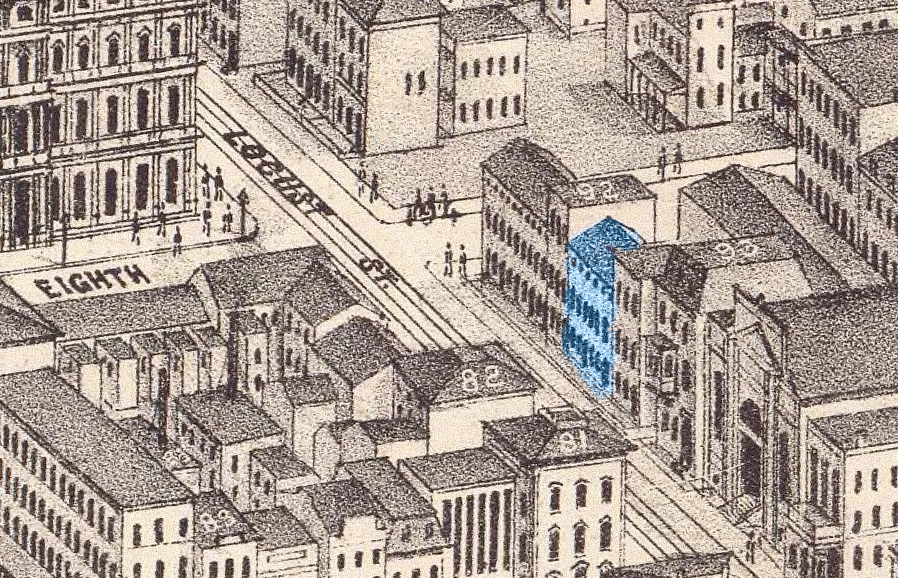

This segment of Plate 2 of the Pictorial Directory depicts approximately 1/20 of the area of that plate showing the west side of Eads Bridge. Consider the level of detail which if multiplied out, makes up about 1/2200 of the entire map. The density of the buildings is certainly less in the less populated sections of the map, but the detail and accuracy of representation and perspective remains.

The Map Layout

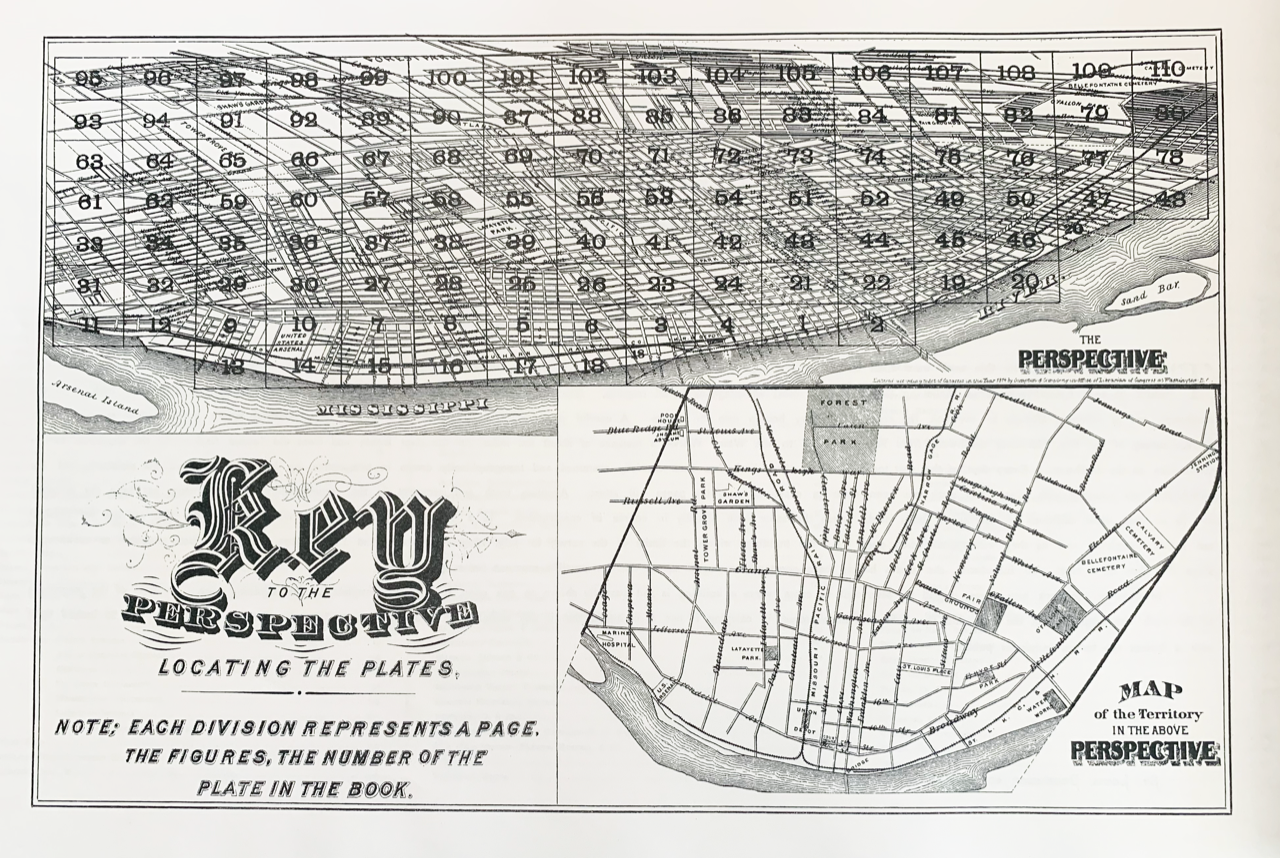

The maps are laid out in 110 sometimes slightly overlapping plates. The plates form a book which also included very interesting details about Saint Louis in 1875 and advertisements of local businesses. The numbering of the plates sometimes seems odd on this grid but the layout accommodates two adjoining plates being seen in the book at the same time. In 1875 the city limits stretched to just about a half block west of Forest Park and Skinker Boulevard, as today.

This 30-foot-wide view of St. Louis from 1875 is part of “Mapping St. Louis History,” an exhibition at the St. Louis Mercantile Library. (Photos by August Jennewein

More of the Impossible to Believe

Another remarkable fact that makes this project unbelievable is even more attention to detail. The original map was drawn as one large mural and then divided up into the 110 segments or plates of 17 by 13 inches each so they could be presented in book form. In order to make it clear where the adjacent pages fit together, each map slightly overlaps the maps on all sides of it. Instead of simply over cutting each plate and duplicating the overlap area, the overlaps were completely redrawn, with the exact same architectural detail but often with new and different inclusions to the drawing such as people, landscaping, street names, etc.

And There’s More…

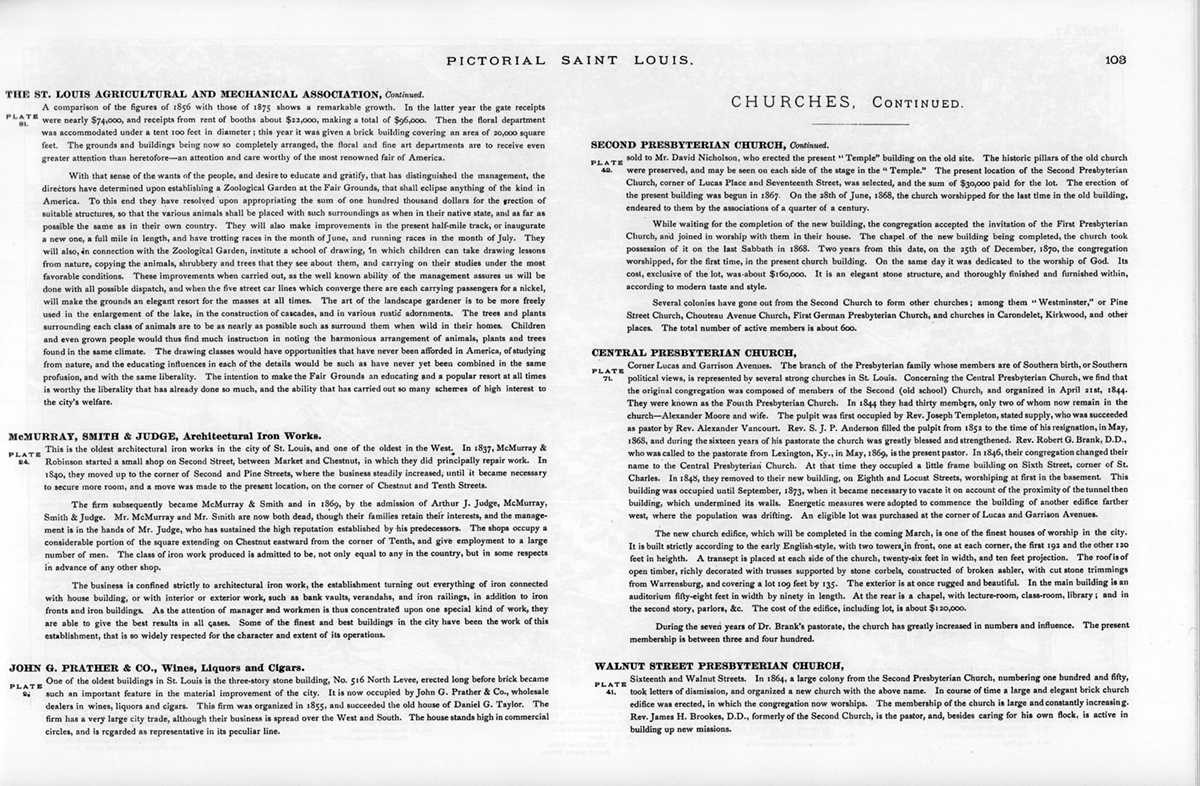

The big book which includes the map plates is made up of 225 pages. The 110 map pages are not printed back to back. Instead, on the back of each map page is a very detailed description of the buildings and people featured on the maps. As is the case with the drawings, the descriptions are comprehensive, accurate and written with a poetic flair making them a delight to read. This exhaustive historical review must have taken a inordinate amount of time to assemble but adds an additional component making this publication of great value. A typical description page is depicted below.

A typical description page which accompanies the maps drawn by Camille Dry. It can be assumed the remarkably accurate and detailed descriptions were assembled by the map books’ publisher, Richard J. Compton, “Pictorial St. Louis – The Great Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley.” As much as the maps, they give us a comprehensive look at life in St. Louis in 1875.

Living for Your Work and In Your Work

During the time Camille Dry was working on this project in Saint Louis he was also living in it. His home was located at Eighth and Locust and is highlighted in the blue on this section of Plate 21. (Distilled History)